There’s no question: middle school and high school bring some of the most trying years of a child’s life. Everything is awkward, nothing makes sense, and nobody understands. Being a teacher for ten years and a mom for 13, I’ve observed children at the various stages of growth and have witnessed the various degrees of “Aaaack!” that come with them. But the common thread, from 12 to 18, is the seemingly innate desire to “fit in.” And, what has pained me the most is not just the lengths to which some will go to do so, but the hurt that comes when it just doesn’t seem to work.

Fitting in. With whom? Why? What is there in us that seems to tell us – sometimes with a whisper, sometimes a shriek – that we are not adequate? Some children are fortunate enough to have built-in defense systems that are able to silence this internal naysayer; but, those who don’t have this force field need something more. They need something from the outside to guide them to value what’s on the inside.

One of the magical things about life is that answers are often hidden, and therefore often come as a surprise. Albert Einstein once remarked that we cannot solve a problem with the same mind that created the problem in the first place. He added, “We must see the world anew.”

It is from this viewpoint that we need to teach ourselves – and encourage one another – to become. And to continue becoming. As adults, we set our own traps, becoming caught in the nets of preconception and status quo. We resolve that because we are this now, we will thus remain, a notion that so often trumps any electric charge of change. How menacing and frightening this idea must be to a generation that wants so badly to belong, and that allows what’s on the outside to dictate facets of its culture like pieces of a puzzle – who fits where?

So, how do we break this cycle of the incessant search for value in all the wrong places? How do we understand that we are enough, and that we all need is to be better today than we were yesterday, and that there isn’t anyone who hasn’t felt less than, and that none of us are ever alone?

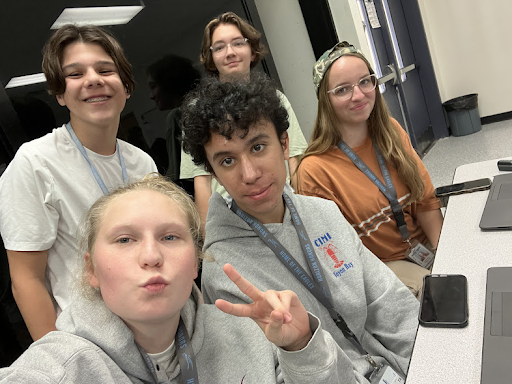

In a recent open-class discussion, one of my students noted that he was able to be himself in our small class. A classmate responded, speculating that perhaps it was because, in that class, everybody was somebody and nobody was nobody. The conversation took on new meaning when the student added that he hadn’t wanted to be in the class – the topic wasn’t the most interesting to him, and he was well aware that his friends weren’t going to be in there – but he was surprised at how well he got along with people to whom, prior to this year, he hadn’t spoken because they “just didn’t have the same friends.” His classmates bring out in him so many facets of his personality that were not necessarily untapped but were most certainly not recognized. He has found family in peers who embrace who he is, and who allow him the freedom and acceptance to become whom he is supposed to be. Those teenagers allowed themselves to see the world anew.

As the mother of a 13-year-old, this is a constant struggle for me. My child’s perception of what I know is not surprising: I don’t understand what she’s going through, and what she’s going through is usually very close to the apocalypse. Sound familiar? I can tell her how beautiful she is and how smart she is and how proud I am of her. But, I’m not the girl next to her in class who has the longer hair or the prettier eyes or the better grade; because of this, as far as she’s concerned, I am an alien.

What we all need when we’re in “that place” is someone who we really believe can relate. Someone important. And, to a teenager, though parents are (of course) important, they often aren’t equated with understanding teenage angst, from wherever it may come.

I can sit here and muse about how to fix what’s broken. We’ve all done it. But among the bumpersticker catch phrases – regardless of how apropos – is a key variable so often overlooked in our formula of righteousness: we – the sayers of sayings and builders of ideas – need to hear the message, too. And we don’t get to decide where or how we hear it, and we don’t get to choose who delivers it to us. We just have to be willing to listen to the words without dismissing them based on what we think we know. This message was delivered to me by the most unexpected of messengers.

Rarely will apathy dominate the response to “Do you Gaga?” I understand the responses on both sides. I do. And there was a time not too long ago that my reply would have been laced with venom. You mean the one who wore a dress made of meat? But, forced to endure the music during our commute to and from school, I started hearing the words. And, to my surprise, there was – hidden among odd metaphors and polysyllabic utterings – a message worth listening to.

Recently, my girl child was given tickets to Gaga’s concert. The star of the show, a just-turned-25 young woman, had turned the culture of our youth on its head. And my child “loves” her. Sitting in our seats, I wrung my hands, not knowing what to expect from this performance. The music was as I had imagined, so I didn’t get really nervous until this eye-catching embodiment of controversy started to speak. But my anxiety dissipated as she delivered a most eloquent reflection. As she talked about being an awkward teenager, I noticed my daughter’s affect shift from one of being entertained to one of genuine interest. This crazily-clad woman had her attention. And she was saying things that mattered. She recalled being bullied and admitted to still waking up in the middle of the night feeling inadequate, regardless of how many thousands of fans were singing her music at that exact moment.

But rather than focus on the pain, she spoke of empowerment. She went on to tell a stadium full of near-silent fans that they were all “born superstars,” and therefore responsible for building their own stages. They – we – aren’t supposed to be what other people want us to be. We aren’t supposed to be anything, but we are the only ones responsible for whom we become. That simple statement sent my daughter to her feet. And I, the initially unwilling concert attendee, followed.

I don’t expect moments like this to remain vivid, always at the surface in our cerebral fishbowls. But I do know that moments like this – whether at a concert, in a classroom, or anywhere – can have an impact. We just have to open our minds and allow ourselves to hear. And to believe.