Dia De Los Muertos: My Journey in Mourning

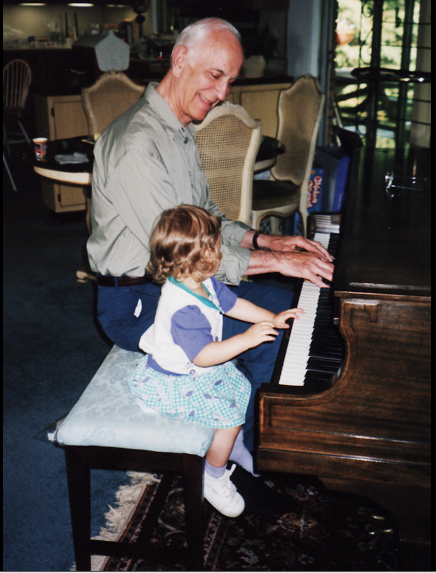

Junior Alexa Geidel sits with her grandfather at the piano. The loss of her hero inspired a reflection of what mourning means along with the crucial role tradition plays in a family.

Even my own mother scoffed at the idea of her obviously European-looking daughter confessing she celebrated Día De Los Muertos. It was a confession because it wasn’t a cultural norm of mine or anyone in my family before me: the heavily German-Irish Geidels and Hardestys. But it was the absolute equanimity that corrupted my small body in the still warm November breeze at my first Día De Los Muertos festival last year that made all the speculation worth it. I had been a part of a parade of individuals coming together to sing joyous Mexican classics in the glow of handheld candles with marigolds tucked between their fingers or behind their ears, mourners laughing rather than crying. That was when I realized this was the solution I had needed all along. Día De Los Muertos became the ultimate outlet for my loss and served as a sanguine way to assuage my heart in addition to realizing traditions don’t have to be passed down, they can also be adopted.

It was the day after the official Día De Los Muertos as celebrated in Mexico and parts of other countries, but I still went to the festival. I went for the sole reason of getting 50 points for a Spanish Beyond Our Horizons project of attending a festival; little did I know I would earn so much more than fifty points from that day. Less than ten months before the festival I had experienced my first ever significant loss. My hero died. It still burns little holes in my heart each time he walks through my mind. Despite my knowledge of every detail of these festivities – trust me, I had done my research – I never fully understood how people could just not cry over a blow so magnificent as a parting loved one.

I had stayed at the festival as long as the day would allow. That night as I watched the park aglow with relatives still raising their candles up to the heavens wane out the back window of my father’s Lexus, I felt something click. It was like the last flake of snow finally landed in the perfect spot to cover the one remaining naked blade of grass. Like when you position your vision flawlessly so a cloud blots out the whole moon. Like when you finally realize there are other ways to feel. Up until then I had tried everything my body could and couldn’t handle in order to procure some new emotion other than sadness in my soul. Could this be it? Could making his stupid favorite German foods be the answer? Could it really be that easy? Yes. Yes it could. I found the answer to all my problems. It was laughing. It was singing. It was remembering the good. Upon this realization, I felt a new emotion. A strange fizziness bubbled up from the recesses of my mind where the light bulbs had burned out so many months ago, and I finally put a name to it: mirth. In that moment, I decided to make this a part of every year of my life I had left, I created a new tradition out of thin and unpredictable air.

Not only was I set on continuing my learning of the Spanish language and culture for the rest of my life, I also set my sights on being a key playing piece in adopting a tradition for the family to come after me. My first and most complete thought was to teach my children Spanish when they start school. I’ve always had my life all laid out like a first-day-of-school outfit. In eighth grade I drew official blue prints of my mansion. That same year, I picked out at least two middle names for all my five children. I always knew exactly what I wanted, but this whole “fostering a tradition” thing had me stumped. How would I get my predecessors to respect my beliefs on this tradition that currently only me, myself, and I celebrated? Old German people are known to open their doors and feed anyone who mentions the smallest bit of hunger, and my beautiful mother was a shining example of this stereotype. So why did she laugh at me when I first mentioned my idea? I decided to put the old people to the side and focus on how to stay true to my own tradition. When I’m 22 and graduating from college or on a Broadway stage, will I remember to set aside the first and second days of November? Or will this be something I only need when I’m in mourning? That’s the thing. When it’s something you only need in mourning, it’s already too late.

I’m already planning on how I’ll spend this Día De Los Muertos: as a party, like it’s supposed to be. It’s about celebrating the good things. Though I still call my hero on his birthday and send postcards to his old house and its new occupants whenever I visit Germany, it doesn’t hurt as badly now that I have something to look forward to.

The day I write this essay is the exact 20-month anniversary of his death. I’d like to think he’d be proud to know that his little blonde granddaughter with huge green eyes adopted a new tradition in his honor. For some reason I’m pretty confident it would.

In addition to writing, Alexa finds her niche in the world of the performing arts. She has studied piano for eight years, sang in All-State choirs and performed in The Nutcracker Ballet. She is a member of the Dance Studio 111 Performance Company Team and the Artistic Director’s Assistant for the Ahwatukee Foothill’s Nutcracker Ballet. She volunteers at her studio teaching young ballerinas. She is president of the ACED club at Horizon Honors. Alexa is in the process of applying to universities across the country for next year.